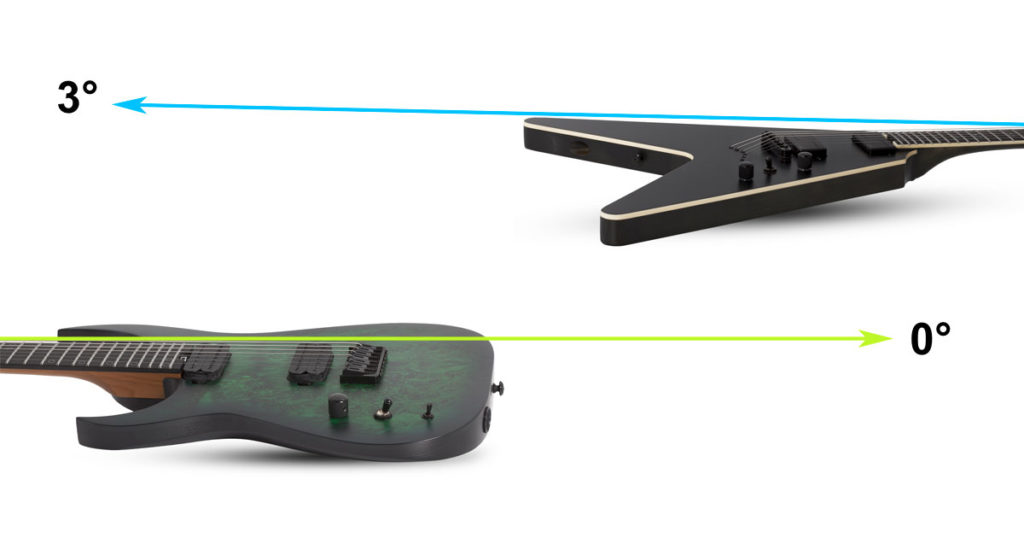

For a beginner guitarist, neck pitch (tilt) is nowhere on the radar when it comes to choosing an instrument. The color is much more important. They’ll eventually discover that different neck pitches change the feel of the guitar significantly, though. It can also have a profound effect on how you play (your sound).

It’s great for players to be aware of this specification and their preferences, but you’re not here to play. A luthier’s understanding of neck pitch needs to go a little deeper.

Why do pitched necks even exist? How are they made? Is a pitched neck superior to a flat plane setup? These burning questions and many more will be answered for you now!

I. The Origin & Purpose of Pitched Necks

The origins of pitched necks has caused a bit of confusion on the internet. A few online sources point to the invention of the electric pickup as the instigating event. Their research suggested pitched necks were a necessity to accommodate the extra bulk of the pickups under the strings. This is incorrect.

Pitched necks are a carry-over from the classical instruments that the guitar descends from. Look at a cello, violin, or upright bass for an example. Each has a pitched neck & fretboard that lift the strings away from the body to meet a raised bridge.

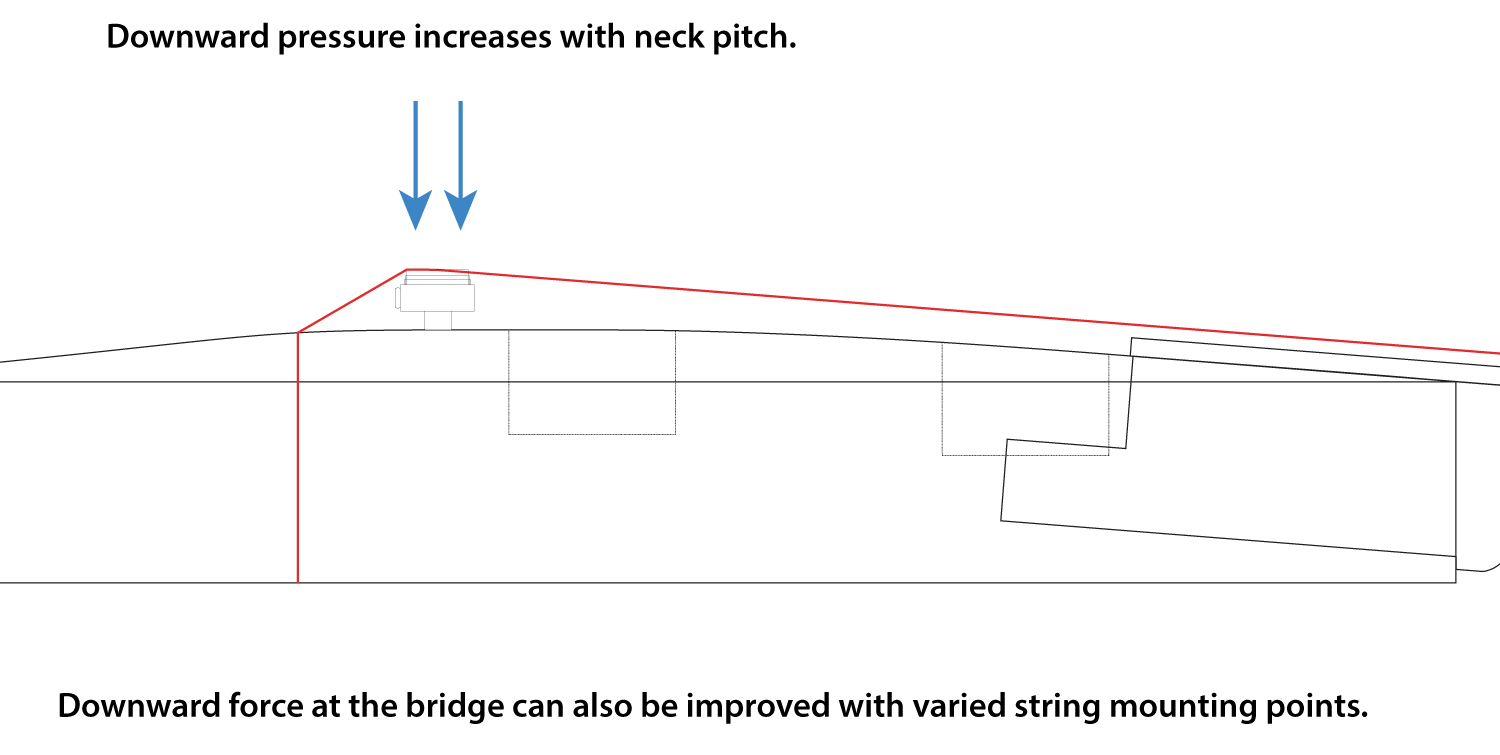

The reasoning for this is purely acoustic. Luthiers discovered that increased string pressure against the instrument bodies improved vibrational transfer long ago.

Downward force is generated with a raised bridge and strings fixed to the body behind the bridge. Modern instruments achieve this with a tune-o-matic style tail piece or string-through ferrules. String vibrations are transferred to the body wood more easily with more downward force on the bridge.

Added pressure allows for louder, richer tones.

The early 1900s archtop guitars are great examples of the transition from classical design to modern electric. This is because you can see the borrowed violin design features very easily. Orville Gibson is one such builder whose work exemplifies this.

Carved single-piece tops and backs, the bridge & tailpiece designs, tilted necks, bracing, f-holes – it’s all there. Keep in mind, the very earliest examples of Gibson’s pioneering archtop guitar designs are acoustic guitars. No pickups to even take into consideration.

So there you have it – pitched guitar necks exist so that the fretboard plane can meet a raised bridge. Together, they allowed for better acoustic performance.

II. Why are pitched necks still around today?

You would think that after electric transducers (pickups in fancy speak) and amplifiers became standard equipment and acoustic resonance was no longer needed, that the raised bridge and pitched neck would be done away with.

Leo Fender felt the same way, which is why he sought to create a flat pitch guitar design. Well, the main reason he wanted a flat neck pitch design was for easier manufacturing. The goal was to get rid of all the extra work that comes with manufacturing traditional pitched necks & joints.

The angled cuts and gluing process that came with manufacturing pitched necks was time-consuming. This was the motivation for Fender to create bolt-on neck designs.

Simply putting the fretboard on the same plane with a simple joint and using a bridge fixed to the body wasn’t enough though. Leo felt that the improved transference of string vibrations of a raised bridge was something he wanted to maintain. The strings were fixed at a lower level than the bridge to create downward pressure. Either inside or behind the body (through holes with ferrule mounts).

You can see another approach to this in Rickenbacker’s designs from the same era. Rickenbacker sought to do the same thing, but unfortunately, his innovations weren’t as attractive as Fender’s.

The wraparound bridge is notable because it fails to generate any downward force. It has the raising action of a tune-o-matic, but vibrational qualities of a fixed bridge.

Why do some guitars still have pitched necks then?

Because there are a number of desirable factors (subjectively) that come with a pitched neck still. It goes beyond simply creating downward pressure on the bridge. Here’s a few arguments for pitched necks:

• Playing comfort

The feel of a raised bridge against your hand is important for some. A raised bridge also creates a spacious picking area. Those with a preference for resting ones’ palm on a pickup ring may find an improvement here. Purely subjective.

• Carved top design preference

Most carved top designs require an elevated string & fretboard plane. A carved top with a flat setup (0° fretboard plane) is perfectly possible, but the results are more subtle. Body contours can be much more exaggerated with a raised bridge and pitched neck.

• Action

Neither of the actions will be definitively better than the other when comparing pitched and non-pitched necks. There’s a few factors that create or affect a guitar’s action. Primarily, the bridge position in relation to the nut, fretboard plane (pitch), and string vibration. A pitched neck is equipped to allow for much more accurate action adjustments by default. String action can be honed through bridge adjustments alone.

A fixed bridge and a flat plane will still have a small amount of play in the saddle heights. Fender found this to be insufficient when reconciling with the string’s vibrational frequency. For this reason, he created the micro-tilt adjustments that you’ll find in post 1970s Fenders. This innovation allows for a very fine tilting back of the neck. The fretboard plane can be brought as close to the strings as possible. This extra action factor is not something that pitched-neck players have to think about. It’s one less adjustment in the setup process as well.

• Improved resonance / tone

Finally, we return to the place we started – downward string pressure on the bridge. There’s no getting around the fact that a stronger joint between the body and bridge will result in better tone transfer. The question is whether or not you subscribe to the idea of tonewood having an effect with electric guitars.

The subject of whether wood vibrations affect the transduced tone can be found in the tonewood article. There’s also the factor of string mounts – tailpiece vs. ferrules specifically. Those are questions for another article.

As you can see, there’s a number of reasons why pitched necks are not going anywhere. Neither is technically superior to the other. Some may argue about the tone, but we all know where that ends up. It’s really down to player preference and comfort. For a luthier, though, the difference is a little more significant.

III. Pitched Neck Construction

Here’s the important stuff. Now you know the reasoning behind pitched necks, you’ll have a much better handle on the construction side. You may come up with some of your own innovative design ideas that Fender and Gibson didn’t think of. They did think of a lot of stuff though, so don’t hold out hope for that.

Speaking of Fender and Gibson, let’s use them as quintessential examples of pitched and un-pitched neck construction. Everyone knows what a Stratocaster pocket looks like since it’s a simple bolt-on part already. But what’s inside Gibson’s glued-in pitched neck joints?

Take a look at the cutaways below for some construction insights:

It’s quite apparent that a typical pitched neck involves a lot more thought and effort. This is one of the difficulties in attempting to replicate the Les Paul design, along with the carved top.

Gibson’s tenon designs vary in length (seen in the examples above). Some have protruding tongues that breach the neck pickup route, others have shorter blocks with less surface area for gluing.

There’s something in common with each of those tenons – none of them have an angled cut on them. The bottom of the tenon is perfectly parallel with the fretboard plane. That’s because the pitch is routed into the tenon pocket rather than on the guitar neck. The neck construction process is easier because of this (in many respects, depending on your tools).

You’ll can see this example in the graphic below (#1):

Another method..

The diagrams above show Gibson’s method of routing the pitch into the tenon floor on the body (#1), while guitars such as the one below simply angle the tenon’s underside plane (#2). Take a look at the diagrams below to see how an Ibanez SZ320’s pitch is built in:

So now that you’re a little more aware of the thought that goes into creating a pitched neck, as well as the purpose behind it all, you may have some ideas for your own model.

Check out the video below to see one a neck pitch being created in the tenon’s (or heel’s) underside, like the #2 example shown above:

Keep in mind, there are still multiple construction methods to build your neck and create your pitch plane. The one above is just one such example.